Progressing on the idea of a tannoy, our group have decided to have the emotional narratives broadcasted outside on either side of the Grand Stand where the original tannoys would have been placed. This not only brings the voice exactly back to where it formerly resided but it also enables the spectators to hear the broadcast without difficulty as it will be transmitted when they are outside the site. The two main narratives that we would like to be played through the tannoy are: firstly about the gambling problems that would have occurred throughout the Grand Stand’s existence, those who lost all their money and those who were addicted to winning. The other is a first person narrative from the Grand Stand’s point of view in the past of what it may have seen during it’s time; such as how busy it may have been, the hustle and bustle of noises that are heard, the different horses which may have won or lost. This narrative carries on to the present time, how the site feels now, the quietness surrounding it and the loss of people which inhabit it. Our main aim of this device is hoping the spectators to question such things as “how did this place come to be as it is; and what will it shortly become?” ((Landscape and Environment Programme, Warplands, http://www.landscape.ac.uk/landscape/impactfellowship/peforminggeographieswarplands/warplands.aspx (March 2013) )) we would like them to reflect on the emotional accounts, understand what has happened to the site and what they believe the Grand Stand should become now they have relived it’s past life.

A journey of our restoration performance has been created for the audience to follow. Starting from the inside of the kitchen area it transports them through the weighing room, waiting room, outside the Grand Stand and finally to the right of it where the perimeter of the two destroyed stands will be re-built. The aim is to initially restore the crowd, entwine the past to the site and attempt to create a future for the Grand Stand. To help the audience to reflect on everything they see we intend to fill as much of the dead space in between everyone’s performance pieces with questions. Questioning what they see, what they think of the past and how it may relate to the present. Only by interacting with the site are the spectators able to each make a decision of its future. Through research it was found that some of the popular suggestions for its future included turning the space into a parcour area, a horse racing themed restaurant and a museum to celebrate Lincolnshire’s history.

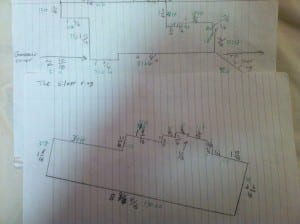

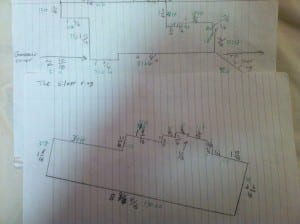

Here are the drawings of the two stands we aim to recreate, with accurate measurements added:

We are concerned with the topography of our site. The tannoy device will assist in imagining the past landscape, very much like Mike Pearson’s ‘Carrlands’ research project in 2008. It took place in three different locations in the valley of the river Ancholme in North Lincolnshire, over the course 0f 12 months. He used three audio works to output his research, each 60 minutes in duration. They included spoken text, music and sound effects, inspired by these locations. The audio accompanies a series of walks at these locations, reflecting on aspects of their history. In Pearson’s piece and much like ours at the Grand Stand “technology plays a significant and transformative meditating role in the response of art to the environment: performance as a medium that can precipitate and encourage public visitation” ((Pearson M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 81)) so through the audio that the spectators can visualise its history. Following from this, Pearson created ‘Warplands’ which was more audio based work that built upon the same approaches he used in ‘Carrlands’. It is also situated in North Lincolnshire; an example of one of the landscapes that was used is Judith’s Bower, which is a turf maze (13 meters across) near the cliff edge at Alkborough. The spoken text in the audio-works are drawn from the work of early topographers, maps and photographs to “illuminate the historically and culturally diverse ways in which a particular landscape has been made, used, reused and interpreted” ((Pearson M. (2012) Warplands: Alkborough, Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, 17:2, 87-95, p. 87)) with the aim of enhancing the public’s understanding of these places. We endeavour to achieve this aim also, to increase the public appreciation of our site. As within our piece “each movement seeks to evoke the particular character of the immediate and more distant landscape: at one’s feet and far off, in both space and time.” ((Pearson M. (2012) Warplands: Alkborough, Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, 17:2, 87-95, p. 87)) We want to bring the past, present and future to the site; with the help of the tannoy the past and present can be brought to life and the public can reflect on this to create a future for the Grand Stand themselves.