Our process started when we investigated Willi Dorner and his belief that to “see the space you also have to feel the space. [Which makes you] feel closer to the city” ((Pinchbeck, Michael (2013) Site-Specific Performance Week Two: Practice [shown at Lincoln: The University of Lincoln. Main Admin Building] [viewed on 3rd May 2013])). From this we investigated the space around us, feeling the architecture and landscape to and learning more about the historical context of the site. We learnt many things about the uses of the site during the war but we wanted to focus on the site during its most in use time and then relate it back to now. Wanting to personify the Grand Stand allowed me to think about the memories the architecture held including how it might feel now, perhaps: lonely, cold, isolated, lifeless, dilapidated, old and broken. We wanted to see how the city engaged with the site, wanting to know their view as to the uncertain future of the Grand Stand. To make it fair for the audience, as a class we realised that we needed to take the audience on a journey through time as well as through the site where it would end with us receiving feedback from the audience regarding their suggestions.

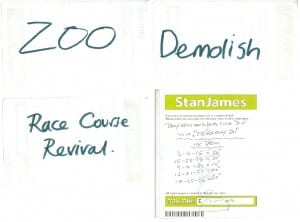

Our performance took place on 1st May 2013 where we presented the audience with plots of the two demolished stands which were made from horse hair twine and 200 suggestions attached to this. The audience explored the suggestions, tracing the plotted stands, taking them in and adding their own. By doing this they were able to walk in someone else’s shoes: those who once were. The audience was able to perceive the landscape as a way of “carry[ing] out an act of remembrance” ((Pearson, Mike (2006) In Comes I Performance, Memory and Landscape, University of Exeter Press. p. 12)). I felt through our performance we were able to carry out this act by showing ghosts of the past intermixed with the infinite amount of future options. On reflection we found the performance to be hard hitting for some members of the audience. On some of the thirty seven ‘demolish’ suggestions they had been tampered with to say ‘no’ and ‘don’t’ which was an unexpected conflict. We appreciated that we were able to impact the audience in such a positive way that it created debate between the audiences.

Our performance developed from our first investigation of the space. We used the technique of drifting as a way of “disrupting routine” ((Goven, Emma, Helen Nicholson and Katie Nicholson (2007) Making a Performance: Devising Histories and Contemporary Practices, London: Routledge. p. 142))where our investigation helped us to re-imagine “the social order of the city into a more fluid and interactive space” ((Goven, Emma, Helen Nicholson and Katie Nicholson (2007) Making a Performance: Devising Histories and Contemporary Practices, London: Routledge. p. 142)). Our perception of the space changed as we learnt more about the history and we realised that the city is “a ‘potential’ space, a place of inquiry and invention” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance, Macmillan. p. 25))of which is free to be explored. Rob Shields states that “a site acquires its own history… connotations and symbolic meaning” ((Shields, Rob (1991) Places on the Margin Alternative Geographies of Modernity, London: Routledge. p. 60)). The Grand Stand is so full of its own history and connotations yet through our investigation we used drifting to get rid of these preconceptions so we could imagine our own.

This documentation of our post-show performance shows some of the hundreds of responses we received. We hope that the legacy of the Grand Stand remains.

Even though our performance and post-show performance has ended our performance similar to the saying ‘how long is a piece of string’… It does not have an end, it is a continuous performance which will outlive the Grand Stand. Upon leaving this project we can only imagine and dream of what is to come of the Grand Stand. Hopefully it will not end up standing lonely and broken but above all, never forgotten by the city of Lincoln.