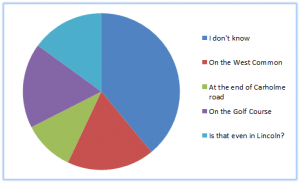

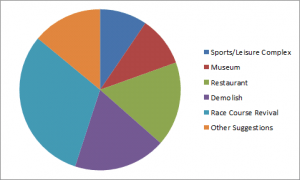

On Wednesday 1st May 2013, we presented to the audience our restoration project. Having set up the two plans, and attached the two hundred suggestions collected earlier in the process, we allowed the audience time to explore what we had presented. As we had expected the audiences spent time looking at the ideas of others before attaching their own. New suggestions were added from what had previously been collected including: a school, nursery, health clinic, interactive exhibit, gardens and a play park. What was not expected was that the audience felt they needed to comment on the suggestions of others. An example of this would be that on some of the 37 ‘demolish’ attachments we found people had crossed some out, drawn disapproving faces or added the words ‘no’ or ‘don’t’. This provides the project with an essence of debate, having audiences interact and disagree with each other, although not foreseen it is still welcomed.

The second part to Wednesday’s performance was the return to the high street. This was not as successful as we’d have hoped because of the time of day. As we had not set up our display until after 5pm, the town centre was not as busy as first anticipated, with most passers-by en-route to return home from their work/school, the majority did not stop to look at the work. Those who did, listened to a brief description of the project and gave us some more ideas. The responses from this demographic of people, centred around evening entertainment facilities, such as bars, clubs and hotels. This for us as a group highlighted the versatility of the site because of it’s size and location.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iC_E1lUh_h0&feature=youtu.be

In reflection finding an end point to this project was difficult. The section presented to the audience during Wednesday’s performance was part of the process, not an end result. Afterwards it was then walked back into the high street, where it continued. We did not want it to just finish here, so instead we decided on a fitting finish for the project. The company which built the Grandstand in 1856, Porter & co, had a factory in Lincoln which has now been demolished, and the site is used as a car-park. We will be taking the completed length of twine and suggestions, placing it at the location responsible for the Grandstand’s very existence. After which, once complete correspondences have been made with the Lincolnshire archives, we would hope to present them with this twine, as the archive building is conveniently located across the street from the old Porter & co factory. This is where we would hope to leave our contribution to the legacy of the Grandstand. An artistic research group called Wrights & Sites created a similar scaled project in 2007 called Possible Forests. This involved the group embarking on a series of reconnaissance drifts through the forest with specialists in diverse fields discussing ways of experiencing, re-imagining and planning the forest landscape. The exhibition documented these dialogues through maps, texts and video, and gave the public the opportunity to contribute their own ‘possible forests’ to the collection. Wrights & Sites explored new ways of interacting with the space around them, and sought after ideas for the future of the forest, just as we did with our project.

As we shared similarities, there is also a correlation with criticisms. Cathy Turner analysed Possible Forests in the Contemporary Theatre Review, in which she examined the relationship between architecture and dramaturgy. “Despite my stress on the provisional and imaginary nature of the architectures proposed by this project it is a small step from here to the production of new architectures” ((Turner, Cathy(2012) ‘Mis-Guidance and Spatial Planning: Dramaturgies of Public Space’, Contemporary Theatre Review vol. 20(2) p.149-161)), which may also be true for our piece. The legislation involved with any reconstruction efforts on a listed building will take local councils a great deal of time to complete. Therefore even if our project convinced the council to begin restoring the Grandstand immediately, it could be years before any changes are put into effect. We can not however, let this dismiss the importance of our work as a potential ignition for change. As well as this we also finished with a great number of suggestions, as did Possible Forests, and this is a positive of both. Turner in the same article writes, ‘despite its open-ended nature, concrete proposals were made’. The idea’s our audiences contributed ranged from practical transformations, to ones that would involve a great investment to change. It is likely that some of the suggestions (i.e. the museum) would have already been thought of by stakeholders of the grandstand, whom hold interested in it’s future.

Retrospectively having more time with the project would have been ideal. Extensive work could have been carried to raise awareness to a larger majority of Lincoln about the Grandstand. Being able to have contact with the council and perhaps the local media, such as the Lincolnshire Echo newspaper, would have enabled for this raise in awareness. Fundamentally the infrastructure is in place for the Grandstand site to operate in any new or past usage, meaning that financial investment would not be as substantial as constructing on empty land. For Lincoln economically, there are incentives to restoring the Grandstand by implementing the suggestions that this project has uncovered.