Within the Book Regeneration by Pat Barker, Rivers describes what it is like to be in the trenches during World War I;

“Groping along the tunnel in the gloom

He winked his tiny torch with whitening glare,

And bumped his helmet, sniffing the hateful air.

Tins, boxes, bottles, shapes too vague to know,

And once, the foul, hunched mattress from a bed;

And he exploring, fifty feet below

The rosy dusk of battle overhead” ((Barker, P. (1991). Regeneration. New York, Plume))

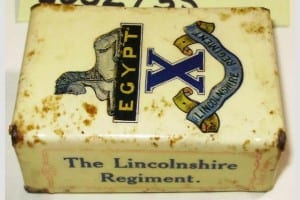

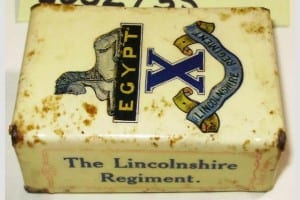

As a form of escapism, many of the Lincolnshire soldiers created Trench Art work. I think the important thing to remember when considering the art is the wide spectrum of media it represents and the vast range of values and emotions it embodies. Trench art is not just the engraved shell cases which is what the majority consider it to be, but it is the full range of mementos that soldiers/servicemen/ locals, refugees or prisoners of war made as a memory of their experience. Trench art could also be considered as a keep sake for loved ones and often made from the materials easily to hand, sometimes the weapons of war, sometimes the rocks and wood they had for walking on – using their craft skills. It is at that point that we consider it was for their loved ones and families or to make a living as refugees, injured soldiers or to express their frustration with the war and the emotions that went with it. The pieces are a value far exceeding that of the materials involved – that the true and often hidden value or significance of the pieces can be found, sadly it is this value that is most easily lost or that has failed to survive.

Trench Art can cover varied materials and pieces including cover sketches, paintings, religious items such as crosses made from bullets, bayonets and many other pieces of discarded military equipment. From manmade materials to carvings in stone, chalk, wood and bone, embroidery and engravings as well as shell cases and regimental buttons and even ink wells and candle stands.

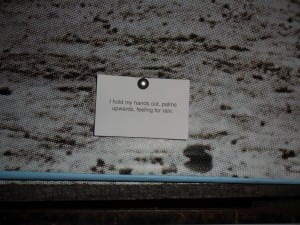

If we take the carved piece of chalk which is on display in the gallery in the archives, it could be described as a form of scrimshaw or simple naive carving, however, in this case you have to ask, where did that individual sit when carving it? How many hours did he spend with his pen knife? Did he do it to calm his nerves sat in a cold wet shell hole or muddy trench under enemy shell fire? Was it done to calm pre attack nerves before going over the top – did he return? Who was it made for and what did it represent for them, what value did it have? For a mother and father, a sweet heart or a wife, a younger brother an injured friend or just something to decorate a locker in a barrack room or just something to waste a few hours before going on stag? So many questions and very few answers but it could have been for all or none of these, what memories did it hold for the maker or recipient in later life – what doors did it open for them or what comfort did it provide. How many weeks did he spend carrying this rock around before finishing it , how many trenches or tunnels did it see?

“Examples of Lincolnshire Trench Artwork” ((Lincstothepast.com (1900) Search results | Lincs to the Past. [online] Available at: http://www.lincstothepast.com/SearchResults.aspx?cmd=type&val=img [Accessed: 10 May 2013))

You can apply these discussions and arguments to almost any trench art object. At another level it is opportunistic recycling, people taking an alternative spin on the objects they have, ingenuity and invention and the artist or engineer or craftsman seeing another use for an object. The steel helmet turned upside down and used as a hanging basket for flowers, the mess tins turned upside down and joined together to make a child’s toy train or items made to maim and kill being mounted to form a cross or table decoration. Weapons of war converted into a simple peacetime use.

Some trench art was commercially made as well, especially embroidered cards and a huge variety of very professionally mass made cards exist – in this it is the written messages on the back that add substance and significance. Likewise certain shell case designs still remain and it was something that many injured servicemen did, selling to other servicemen, to make money to survive.

In essence every piece of trench art has its own story, it is individual, has its own poignancy, its own value to the people that made it, gave or received it, treasured or cared for it. Some of it was anti-war, some of it very much celebrates the victories, and all of it is deeply rooted in the raw emotion of the time in which it was made. Taking this on board, for my piece, I have been given artwork and a poem by www.lincstopast.com The artwork is by general Lincolnshire Soldiers but the poem is By Private Charles Tear, 138th Brigade, M.G.C. Within the poem he discusses men from Lincolnshire including William Rainsforth, the 1st man 2nd row from the back – to the left in the Machine Gun Section of the 5th Lincolnshire Foreign Service Territorial Regiment – 13th October 1915 – before the battle to take Hohenzollern Redoubt. Here is a snippet of the poem;

Boys of the Old Brigade

The boys I’m going to write about,

Though not up to perfection,

I’m simply paying a tribute

To the veterans of our section. ((Online:http://www.wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/allied/lincolnshireregiment.php#sthash.6b6rL9Os.dpuf, accessed 4th March 2013 ))