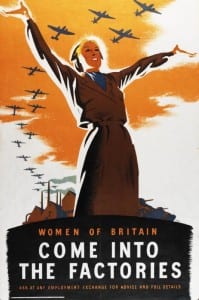

Following onto the idea of women during the war, I have been focusing on the war posters. They were created during World War One and Two in aid of advertising the recruiting of jobs. Women before the war were known to be classed as housewives in which stereo-typically they did jobs such as nursing. It changed when the war began, men had to go to war and fight where “women were called upon to fill their jobs” (Barrow, 2011). For example factory work, farming, mechanics and engineering. So in order to help the soldiers, they had to do the work. There are many war posters around but this particular one stood out to me. The reason why it did was because as a group we are focusing on the war, especially in our sub groups; women of the war. The strong stance from the woman shows an invitation to others to come and help the men at war, and with the aeroplanes flying over it shows a representation of what she has done in able to help them.

(http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~pv/pv/courses/posters/images1/womenfact.jpg)

With the aeroplanes flying over head, it links in with Emily’s, Phoebe’s, Sophie’s and I’s idea on focusing on the making of the aeroplanes wings. I want to be able to create this image during the performance. Gabby came up with the idea of smashing cups and plates to represent the Roman pottery, which her group had found during their investigation of the site. I want to be able to use her materials and make the image of the poster above as a mosaic. The artist that inspired my idea is Mark Storor, he created a piece called “Our Caravan”. It is a “caravan completely mosaiced on the outside with broken china and filled with tea and an abundance of bakewell tarts” (Addicott) This installation was exhibited in firstsite gallery in March 2003. Whilst participating in a workshop with Mark himself. He showed us many art projects that he had created and the idea of the mosaic caravan stood out to me the most as it is a simple piece of art but it can have many ideas behind it and this is what I wanted with the outcome of the poster I will create.

Works Cited

Addicot, Matt. Workshops/ Matt Addico, Online: http://mattaddicott.com/MAWorkshops.html (accessed 13th March 2013)

Barrow, Mandy (2011) Jobs for Women during the War/ Britain since the 1930s, Online: http://www.chiddingstone.kent.sch.uk/homework/war/women.htm (accessed: 13th March 2013)