Our concept was “inspired by…the characteristics of the place” ((Pearson, 2010, p.148)) it gave us our concept as McLucas comments “deciding to create a work in a ‘used’ building might provide a theatrical foundation or springboard…it might get us several rungs up the theatrical ladder before we begin” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p.149)). In terms of Brith Gof’s considerations of the ‘host’ and the ‘ghost’, the building was such an imposing host that regardless of what the ghost was that we brought into the site, the host and the ghost would begin to “bleed into each other” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p.149)) and therefore the site would heavily influence the performance. As, even though the site had been emptied of the majority of its paraphernalia which had been left behind when it closed in 1965, there were still a large number of traces of what the race course once was. There still remained the old weighing rooms, and remnants of the old course. These were all part of the “fixtures and fittings” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p.35)) and from this we wanted to create something that would become, as McLucas calls it, a hybrid of performance 20 which combines the “performance (ghost), the place (host) and the public” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p.143)). We wanted to make the piece specific to the site in some way whether that is in “subject matter, theme, and dramatic structure” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p.149)). We wished ultimately to explore the notions of site-specific performance in our work and where our performance could fit into this field. We wanted the site to be a central influence to our piece and using it as our primary stimulus for devising helped us in this. We started our devising process similarly to Pearson’s process with “a process of research, frequently interdisciplinary research: into site and subject” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p.151)).

After doing our own separate research and finding key areas of interest, we, as a group had a turning point after visiting The Lincolnshire Archives, ‘of over 50,000 men recruited into the Lincolnshire Regiment during the First World War, almost 9,000 were killed and at least 30,000 more were wounded, gassed or taken prisoner’. The sheer quantity of Lincolnshire men that died shocked our group and we decided to make this our focal point. Researching further we found an estimate of the amount of money which was given to the soldiers as a ration, one penny. Using these two strands we decided to construct an installation piece of artwork with 9,000 pennies, portraying 9,000 lives. We decided to do this by creating a giant Union Jack which was found in the Lincolnshire Archives, the flag was created by a Lincolnshire man; in essence bringing Lincoln’s heritage back to the Gateway of Lincoln.

The idea of using the coins also links directly to the site; the idea of placing bets, this although sticking to the conventions of the site also brings fantasy into the piece with the idea of War being a theme, much like Gob Squads work in 1995. We wanted to create an installation piece of work that the audience could be involved with by allowing them to place down coins as well as the ‘performers’ doing it. Whilst doing this we decided to also read out facts that we have researched; The Beechy boys story and the facts about the artwork, this will enable us to create poignancy and much like Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Relational Aesthetics below we are placing the lives of the soldiers in a live social context (performed) rather than it being kept in a private space (kept as a fact)

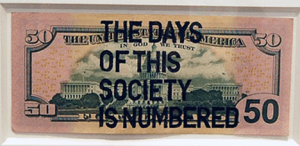

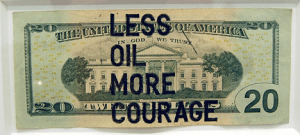

“Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Relational Aesthetics” ((Weburbanist.com (2008) Amazing Collection of Artworks Made From Money | WebUrbanist. [online] Available at: http://weburbanist.com/2008/12/14/art-from-money/ [Accessed: 10 May 2013].))

Rirkrit Tiravanija is a Thai contemporary artist known for exploring the social role of the ‘artist’ using the ideology of relational aesthetics. The artwork creates a social environment in which people come together to participate in a shared activity, the idea of creating a piece in which the audience can participate is an idea that we want to include. Bourriaud claims “the role of artworks is no longer to form imaginary and utopian realities, but to actually be ways of living and models of action within the existing real, whatever scale chosen by the artist.” ((Bourriaud, Nicolas, Caroline Schneider and Jeanine Herman. Postproduction: Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World. New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2002.)) In Relational art, the audience is envisaged as a community, rather than artwork being an encounter between a viewer and an object, relational art produces intersubjective encounters. ‘Rirkrit Tiravanija is most famous for installation art pieces where he cooks meals for gallery-goers, reads to them, or plays music for them. However in this piece he used money in order to create a reaction from his audience. Rirkrit’s treatment of money, above, is a perfect example of the examination of human beings in their social context rather than in a private space’. ((Weburbanist.com (2008) Amazing Collection of Artworks Made From Money | WebUrbanist. [online] Available at: http://weburbanist.com/2008/12/14/art-from-money/ [Accessed: 10 May 2013].)) Much like this art work we want to use the coins to send a message – to highlight the vast quantity of men that died from Lincoln to protect our country.

Another Practitioner that we have taken inspiration from for our Piece is John Newling’s ‘Ecologies of Value’ in which he used explored the social and economic system of society with 50,000 two pence coins; much like our installation piece he replicated a static object (a cash machine) but also related his artwork to the act of taking communion in the Christian church. This idea of using two themes relates to our work with the aspects of war and betting creating one united installation. These ideas further link to Higgins and his theory of how artwork links what is understood to what is not ‘The concept is understood better by what it is not, rather than the what it is’ ((Higgins 1969:25)), much like Higgins and Newling the piece is more focused upon conceptual art, as the group is more focused upon the ideas presented compared to the finished article.