With the recitation of the poem, I originally felt that performing the poem 1 to 1 would create the greatest possible experience for the spectator and myself to share together. I researched the concept of 1 to 1 performance and came across the following – “Solo performance can draw together narratives… can play a generative role in interpretation and the creation of new ways of perceiving; animating through fiction…. Solo performance can include truth and fiction, lying and borrowing: the fragmentary, the digressive, the ambiguous… It can include traveller’s tales, poetry, forensic data, quotations, genealogies, lies, jokes, improvised asides, physical re-enactments and autobiographical details.” ((Pearson, M (2011) Why Solo Performance? Online: http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/landscape/impactfellowship/peforminggeographieswarplands/toolkit.aspx date accessed: 12/03/2013)) This quote opened up the options of what I could potentially include in my performance, and also presented the new idea that performing 1 to 1 can create “new ways of perceiving…” ((ibid))

When I next visited the site with the class I did a run through of the poem, and I discovered that while performing the poem 1 to 1 did create an incredibly strong connection between myself and the audience member, it was not practical to perform the poem 1 to 1 within the context of our group performance. This was because if we had a large audience visit the performance, not only would they have to wait in turn to hear the poem, but then after that they would have to wait before they could move on to spectate the next part of the group performance. Although this would have tied in with the original theme of waiting which my first blog post was about, due to the confines of the time frame we had booked the site to hire for the performance, performing 1 to 1 would not be possible. I decided it was best, with regards to the time constraints, if the audience as a whole heard the poem together. I also added in the use of music during the poem, in aid of enhancing the emotional connection which the 1 to 1 performance created. This was done by collaborating with another member of the group who could play the tenor horn. They played The Last Post, to which the poem repeatedly references.

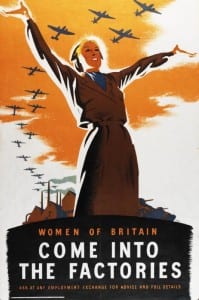

During this visit to the site I also discovered that there was another member of the group who wanted to show the Military history of the site through their performance and we began to work together on a short piece which would not only introduce the performance, but would also introduce the audience to the rich Military history of the site. We decided that one of us would present the World War One history and the other would present the World War Two history of the Lincoln Grandstand. As I had a lot of research regarding the Military history of World War One I decided that I would take care of the First World War performance.

We decided that we would begin by bringing the audience into the weighing room of the Lincoln Grandstand, addressing the audience together and introducing them to the performance. We would then split the audience into 3 groups. One group would go with the World War Two history, one group with the World War One history, and the last group would go with the T.A.N.K group. After the audience had experienced one of these 3 performances, they would be rotated to experience another. No audience group would see the same performance twice.

I decided that this would be the perfect time to bring the golf bunker into the performance. The bunker would be used as a trench. I gathered 50 small bags together, went outside to the bunker and filled them with dirt from the bunker. The performance would consist of me performing solo, giving each audience member a bag of dirt and I would then take the audience outside and lead them to the bunker. The audience would play the role of soldiers and I would be training them in the use of the trench. I would tell the audience to get in the trench, be told about the use of the trench and then be tested in some duck and cover drills. The bags of dirt would then be poured back into the bunker one at a time by the audience members as they said their name and place of birth. This would be the introduction of the concept of becoming one with those who had gone before them. By helping to ‘build’ the trench, the audience would join the soldiers who came before them and would also become amalgamated in the First World War history of the Lincoln Grandstand.