Offering the audience juxtaposing views of the Grand Stand has been the groups aim throughout. With the senses of smell and taste being tantalised with food and drink in such a damp and dirty environment and people being brought into a space that is so dead, we already offer contrasting views of the space. To take this further the group needed to attain a specific space with the Grandstands weighing room to work with. Since we wanted to create a ‘factory’ environment, using our sewing machines to exhibit the work of the women in Lincoln during WWII, we needed a space that was mechanic, cold and quite harsh. The room that the group were instantly drawn to was the bathroom. With its exposed urinals, singular shower cubicle and revealed boiler it created the effect that we needed. On further inspection there are open pipes, holes in the walls and uneven surfaces which work well to juxtapose the bustling factory environment, created with the piece, with the abandoned building that the group are actually working in and with.

Coming to the Grandstand, the group made sure to remember that they are actually strangers to the space, and pondered on the question as to how long they would remain in that status. Being strangers, it could be difficult to really understand the space and its design, uses and history without really thorough research. For the Women at War group this was not so much of an issue. The toilet space had an obvious use, it was a bathroom, somewhere to relieve oneself, to powder the nose and even to taken a shower after a race. It was apparent that the facilities (especially the shower) were not regularly in use, the cobwebs and dirt had built up over time. However, although we were familiar with the uses of the space, we were still strangers to it. We therefore wanted to play with it in a juxtaposing way. Placing lipstick, perfume and toiletries around, their scent alongside the smell of freshly brewed tea, so that the “Scents mingle and intertwine” (( Curious (2003) On The Scent, Online: http://www.placelessness.com/project/1121/on-the-scent/ (accessed: 19th April 2013 )) as we wanted to offer a new viewpoint and use of the space. “The strangers’ perspective may result in the space itself appearing strange to the spectators as the visiting artist offers up new understandings of the location and practices within the site” ((Govan, Emma et al (2007) Making a Performance: Devising Histories and Contemporary Practices, London and New York: Routledge)) Our new understanding of this masculine place full of decay and rot as a feminine one, full of tea and productivity, will hopefully provide that strange and confusing atmosphere for the audience to take pleasure in, finding meaning from the semiotic of giving, and taking away the tea.

Month: April 2013

T.A.N.K Part 4 – Smaller on the Inside

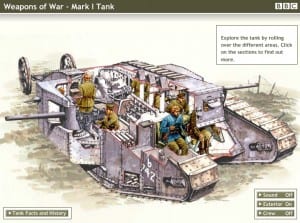

When it came to rehearsing our section, now that we had created the caterpillar tracks added some movement, applied some text to the movement, what should we do next? What more could do to give the impression that the audience were seeing a tank from the First World War? After a another trip to the museum of Lincolnshire life and reading more into what it would have been like for the crew inside the tank. The idea that we came up that we should place our audience on the inside of our caterpillar tracks, placing a piece of material over them like a roof and squeezing the audience together to give that Claustrophobic feel that they are inside this killing machine with no way of escape.

The original Tank crew shared the same space as the engine. The environment inside was extremely unpleasant; since there was no ventilation, the atmosphere was contaminated with poisonous carbon monoxide, fuel and oil vapours from the engine, and cordite fumes from the weapons. As you can see from the video it was a claustrophobic space for someone to be in, although they were protected from any outside force, it was the inside that was more deadly. The crew themselves were only issued with leather-and-chainmail masks plus a helmet to protect their head against projections inside the tank. Gas masks were standard issue as well, as they were to all soldiers at this point in the war.

Steering a tank was difficult; it was controlled by varying the speed of the two tracks. Four of the crew, two drivers and two gears men were needed to control the direction and speed. As the noise inside was deafening, the driver, after setting the primary gear box, communicated with the gears men with hand signals, first getting their attention by hitting the engine block with a heavy spanner. For slight turns, the driver could use the steering tail: an enormous contraption dragged behind the tank consisting of two large wheels, each of which could be blocked by pulling a steel cable causing the whole vehicle to slide in the same direction. If the engine stalled, the gears men would use the starting handle – a large crank between the engine and the gearbox. Sadly many of these vehicles broke down in the heat of battle making them an easy target for German gunners.

Now that we had an idea of what we wanted to with the audience, we decide to apply some more text to our piece, this time it was instead of the tank crews motto, we were going use the a newspaper article form the Lincolnshire echo from 1965 entitled ‘Men and Machines’. The article itself was someone opinion on how we now relying on machines to do our fighting instead of an army.

“The improvement in machines far outstrips the improvement in a man as a fighter as so we become more and more mechanized”

Works cited:

www.firstworldwar.com/weaponry/tanks.htm (Accessed 14th April 2013)

www.bbc.co.uk/history/interactive/animations/mark_one_tank/index_embed.shtml (Accessed 19th April 2013)

Linconlshire Echo,Men and Machines,1965

Penny for your thoughts?

Every

Penny

Helps

Adele Prince is an artist based in London who works on a varied amount of projects based around the idea of durational art, through the use of media including the web and moving image. A piece of her artwork which links directly to our piece is called Lucky World. Lucky world involves the use of pennies, with the ideology of ‘find a penny, pick it up and all day long you’ll have good luck’ she began this process by picking up seven pennies and creating a journal of her luck for seven days. She then distributed the coins for other people to do the same, and they too would fill in their own journals using many forms, including pictures and written evidence. This piece links to our group through the audience participation and the idea of having them bring a penny to the piece to ‘donate’. Although they are considered as a spectator within our piece, they are also considered a performer as stated by Cathy Turner ‘every audience member has a vast range of perceptual roles at their disposal: theatre spectator, tourist, game player, partygoer, voyeur, connoisseur, witness, scientific observer, detective. ((Turner, C (2000) ‘Framing the site’, Studies in Theatre and Performance, Supplement 5, pg. 25)) The idea of bringing a penny also symbolises the journey that our research has taken to reach the point of performance, much as a penny shows it journey through its shine or its dents, its rust and even the dating upon it. We want to show how we are still affected by the losses of War and the Grandstand being what it once was. To achieve this, we are initially setting out many of the coins to represent the many lives that have been lost but by asking the audience to bring a penny we are spreading our knowledge to the masses, and highlighting how it is still relevant to today’s generation with the Iraq War and even Margret Thatcher’s funeral. The funeral included 700 troops due to their involvement with her in the Falkland’s war; this therefore shows how the theme of our piece is current to todays’ ever changing society.

By placing the penny with the Queens face facing upwards we are again reminding the audience of the ideology of the war theme running parallel to that of the Site. The ideology of fighting for the monarch and country is visible through the placing of the coins face up, hopefully conjuring the image of medals such as The British War medal, given to brave soldiers during the First World War.

“Every man must decide whether he will walk in the light of creative altruism or in the darkness of destructive selfishness.”

This quote stated by Martin Luther King Jr highlights our groups’ opinion towards the use of the coins within our piece, after spending time collecting donations from various people and spending a week visiting multiple banks we are finally reaching the target of 9000 coins. Each member of the class has given £3 and as a group we had realised and have come to appreciate the amount of money we have raised for a performance. Would we leave the coins as dead space? Should it remain dead space like the Grandstand, unused and unwanted, or, should it be put back into the community?

We decided with the help of the fellow donators to donate the money to two charities which are best associated with our piece, the charities we have chosen are; ‘Bransby Horse, rescue and welfare’ this is a local charity, which has two bases and one of which is in Lincoln. This charity is concerned with providing a sanctuary for abused equine based animals and re-homing them’ ((http://www.bransbyhorses.co.uk/home/home%20about%20us%20NEW.html))

The Second Charity is; ‘Scotty’s Little Soldiers, this charity helps to support the children of the serving/fallen soldiers’ ((http://www.scottyslittlesoldiers.co.uk)) We feel that by donating the money to charity we are keeping the project and the performance alive, and in turn commemorating the soldiers and horses that have fallen from Lincoln.

Becoming a Woman of War

‘The movement of many men into the military and women into occupations previously undertaken by men is seen variously as bringing about permanent changes in gender roles, as illustrating the rigidity of gender relations, and as a significant element in individuals’ personal narratives of their own lives.’ ((Noakes, Lucy (2007) ‘Demobolising the Military woman: Constructions of Class and Gender in Britain after the First World War’, Gender and History, XIX (1), April pp. 143-162.))

The women of war were depicted across the country in propaganda posters, showing strength, bravery and fearlessness. In many ways, this portrayal was just. Fashion seemed to change from pretty to practical allowing women to throw themselves into the work place, from factories to the fields. However this generalisation does not take into account the importance of femininity: ‘A bright slash of lipstick, softly waved hair and a lingering trace of perfume could be seen to represent the persistence of the feminine in a masculinised world of war, a sparky message of defiance, a feisty semaphore of hope.’ ((Gardiner, Juliet (2004) Wartime Britain 1939-1935, London: Headline Book Publishing, p. 578.)) Clearly femininity was regarded to be highly morale boosting, possibly because it represented normality and familiarity in a country turned on its head, but more simply because it was something beautiful in a place of destruction. ‘Wartime discourse was complicit with the idea that a beautiful face was a brave face.’ ((Ibid, p. 579)) In addition, cosmetics were never rationed (although they were in very short supply anyway) ‘because the government recognized their morale-boosting properties for a female population who had few other opportunities to express their femininity and individuality.’ ((Ibid.))

Taking this into consideration, we feel that it’s necessary to present typical wartime fashions, such as the red lipstick and 1940’s style tea dresses. Our sub-group has two sections that will show a juxtaposition of femininity within a masculinised setting. Our first section starts the audience’s journey around the piece. We are serving tea and cake to the members of the audience- a stereotypically feminine role, but it will hopefully connote a feeling of community and a picture of the past. Our second section shows the transition of women into the war environment. For many, this period was of great change: ‘During the war, for the duration, new sets of beliefs about women, their capabilities and responsibilities emerged.’ ((Goodman, Philomena (2002) Women, Sexuality and War, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave, p. 15.)) This was the start of women being able to show not only men, but also themselves, what they were capable of. So, at the end of the weighing room we will set up a sewing factory style scene, involving a repetitive series of moves between the four of us in the scene. There will be two sewing machines set up- we hope that the mechanical and repetitive sound of these, in addition to the industrial feel to this section of the room will juxtapose with our costumes and we also plan to have classic war-time songs, such as Judy Garland, in the background.

The sewing itself is a significant aspect to our piece- the need to ‘Make Do and Mend’ was of great importance when clothes rationing was put into place in both the first and second world war. ‘Helen Johnson, aged ten when war broke out, remembered how: ‘because of clothes rationing we had to make do and mend. So we would beg old dresses from our mothers or aunts and try to renovate them to make them fit.’’ ((Ibid, p. 102.)) As a group we want to translate this idea by collecting clothes that have been donated to us, or our own clothes that we don’t wear anymore, to make a patchwork piece of material that stretches through the weighing room, suspended from the ceiling. During the piece we will be adding more and more to the material. Visually we were inspired by John Newlings’ Where a Place Becomes a Site: Values– Newling suspended a jacket covered in question marks, such like the infamous Riddler’s Jacket from Batman, from the ceiling of Nottingham’s Broadmarsh shopping centre and asked the public what they most value in their everyday life. The patchwork style will also be echoed in our own costumes, as we will be making pinnies in the same style.

Another layer to this is that we found, from The Lincolnshire Archives, that women would help to sew linen to the wings of aeroplanes during the war. This also helped with the visual aspect of the material being suspended from the ceiling, showing a sense of grandeur, and connoting the women’s work being high above us in the sky.

In summation, there is definitely an importance in celebrating women’s femininity within a masculine world, and what war meant for women. ‘Women were already beginning to enter the workforce in greater numbers before the war. But what might have been gradual and quiet progress into many previously all-male preserves was thrown centre stage with the direction of female labour into key areas.’ ((Harris, Carol (2000) Women at War 1939-1945: The Home Front, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd, p. 62.)) This shows that war was a catalyst for the change of gender roles in society. Within our piece we want to put forward that women ‘had the opportunity to colonise male space, to achieve their potential in the public domain, to achieve self-determination and perhaps, in some cases, to challenge inequality.’ ((Goodman, Philomena (2002) Women, Sexuality and War, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave, p. 103.)) But fundamentally, we all want to make do and mend the Grand Stand.

Scent.

From the first time that we as a group stepped into the Grandstand building we were intrigued, bewildered and passionate. Knowing that this space had such an overwhelmingly rich history but was, unfortunately, so unused at the present time was a shocking and inspiring juxtaposition.

War is a recurring theme within our group. The Grandstand had such a role to play within the 1st and 2nd world wars, it was involved in army training, and trench practice and it was also closed during both of the wars. This led me, Jamie, Sophie and Phoebe to think about the women that would have been associated with the Grandstand before the wars and during the wars. What would have happened to the women that worked there? Are there any parallels between them and the women that use the Grandstand now?

We began looking at involving the audience’s sense of smell within our pieces, taking inspiration from reminiSCENT by Jim Drobnick in which he explores the relationship with scent and memory “If the sense of smell appears to be eclipsed by the other senses in western culture, there is one realm in which it retains an almost mythic power – memory” ((Drobnick, Jim (2009) ‘Sense and ReminiSCENT: Performance and the Essences of Memory’ , Canadian Theatre Review, Issue 137, Winter: p.6-12)) At first we thought that using a perfume that the women of the Second World War would have worn and spraying it on letters would be effective in taking the audience on a journey through time, we experimented with this somewhat. However, as our research deepened we decided that we wanted to instead, take the audience on a journey back to when the Grandstand was alive and bustling with people “As much as smells conjure memories, they also conjure places” ((Drobnick, Jim (2009) ‘Sense and ReminiSCENT: Performance and the Essences of Memory’ , Canadian Theatre Review, Issue 137, Winter: p.6-12)) , We discovered that they would serve gingerbread and fruit to the crowds of spectators at the Grandstand, which would have created an aroma specifically related to the atmosphere of the races.

Another level of scent that we wished to include was that of tea. We know that the Grandstand is currently being used as a sort of ‘community centre’ and we found teacups saucers and a kettle on the site therefore there will probably be tea being served regularly. Since “tea is –after water- the most widely consumed drink in the world”(Deadman,P (2011) ‘In Praise of Tea’ Journal of Chinese Medicine, October: 14-8)) and has been in available in Europe since 1606, almost everybody can relate to the smell. Within Britain it is the drink associated with home and comfort, community and togetherness. Therefore we decided that it was essential to combine the audiences personal memories of community based activities, with the imagined atmosphere of the day at the races. This not only links together the site with the performance but also the past, present and maybe even future of the Grandstand through scent alone.

This research helped us to create a part of the piece so far in which we aim to combine the image of the women working at the Grandstand previous to war, having to leave and abandon their ‘normal’ tasks, to contribute to the building of aeroplane wings or to join the WAAF. This is something that would have happened to the women of Lincoln during the war; it disrupted the community and changed the way the Grandstand was used. We have tried to do this by creating layers of emotional and memory evoking material using scent, visual aids and sound to devise an effect such as the one Cage talked about in Kostalanetz; “I would like the happening to be arranged in such a way that I could see through the happening to something that wasn’t it”(Kaye, Nick (2013) Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place and Documentation, London and New York: Routledge)) We want the audience to achieve this level of vision when interacting with our piece. The scent of the piece should be the first thing that hits our audience as they walk through the doors. The mixture of tea, gingerbread, fruit and the damp of the unused building will mingle together to form a potent aroma, representative of all of the different aspects of the overall performance narrative.